Introduction

Increasing seafood purchases, is a solid strategy for reducing meat while promoting human and environmental health. However, the lack of transparency – along with seafood’s numerous health, environmental, and social justice concerns – make it a particularly difficult food group to navigate. This guide offers seafood procurement recommendations based on sustainability, nutrition, social, and animal welfare concerns.

This guide’s recommendations complement existing third-party certifications and inform day-to-day purchasing when sustainability labeling and information is limited.

Our recommendations

|

Seafood purchasing considerations

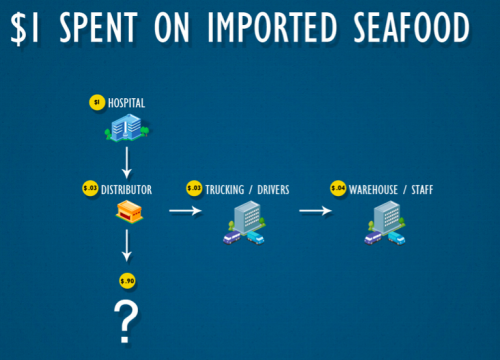

Ninety percent of the fish people in the United States consume (by edible weight) is imported, including domestic varieties processed overseas. The United States exports most of its highest quality wild fish to other countries and imports mostly farm-raised fish, both for cheaper prices and to satisfy the high demand for the limited species commonly consumed in the United States (e.g. salmon, tuna, shrimp). Less than 2% of imported seafood is inspected, raising concerns about the traceability of production, harvesting, labor, and food safety practices.

Health care facilities should aim to purchase a wide variety of seasonally available fish, and prioritize less commonly consumed species. Purchasing less common species is a triple win. It provides income to fishing communities for species that are harder to sell; it takes the burden off of the most commonly consumed species, allowing their populations to rebound; and species in lower demand tend to be less expensive for health care facilities to purchase. Many uncommon species are just as delicious as common species and they can easily serve as substitutes in dishes like fish tacos or fish and chips. Mollusks (clams, mussels, oysters, and scallops) and small forage fish (herring, sardines, and anchovies) have particularly low and sometimes beneficial ecological footprints. Look for underutilized, wild varieties available in your region to replace more commonly purchased seafood.

Half of the seafood that the United States imports and consumes comes from aquaculture. Aquaculture is the farming of aquatic organisms – like fish, shellfish, and even plants – for consumption or other human use. The term aquaculture refers to the cultivation of both marine and freshwater species and can range from land-based to open-ocean production.

Practice Greenhealth’s purchasing standards consider aquaculture operations sustainable only in the cases of mollusks and seaweed / kelp. The leading third-party certifier, Seafood Watch, does qualify some varieties of farmed finfish as sustainable. However, Health Care Without Harm’s analysis concluded that the impact from so-called “sustainable aquaculture” on the ecosystem continues to pose threats to the livelihoods of U.S. small-scale independent fishing communities. Seafood Watch’s assessment does not take into account the impacts on the small-scale, independent fishing industry.

We recommend that all purchasers consider full dietary composition to align with the benefits of a systematic environmental nutrition approach.These considerations align with findings detailed in “Redefining Protein: Adjusting Diets to Protect Public Health and Conserve Resources,” Health Care Without Harm’s report that summarizes and analyzes academic literature on the impacts of whole food protein options, with an emphasis on legumes, nuts and seeds, eggs, seafood, and dairy.

Is your seafood sustainable?Practice Greenhealth considers seafood to be “local” if it is grown/raised/harvested/processed within 500 miles of the facility. Bivalve seafood (e.g. oysters, clams) from wild or aquaculture operations or wild finfish that are harvested and processed within the local definition can be counted. However, any finfish from aquaculture operations are disqualified from local or sustainable designation. If you are not located in a coastal community, explore sustainably caught freshwater fish or buy domestically caught wild species that are certified by a third party. For more information, refer to our healthier food purchasing standards. |

How to establish your purchasing priorities

There is not a one-size-fits-all preferred seafood production system. However, you can develop purchasing priorities and creating a plan that aligns with your values. In addition, you have the opportunity to use your purchasing power to support local fisheries and encourage market growth in sustainable fishing practices.

Below are several examples of seafood production systems that align with values. Different production systems are better at addressing a particular value than others.Least GHG emissions: wild-caught, particularly bivalves, like oysters and clams Best nutritional quality: wild-caught, species-specific

Least concern for persistent organic pollutants or mercury: wild-caught varieties other than shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish or farm-raised varieties

Least impact on ocean ecosystem: wild-caught varieties

Least need for inputs (such as antibiotics): wild-caught varieties Least need for synthetic pesticides: wild-caught varieties Best impact on biodiversity: wild-caught varieties, underutilized varieties

Best community economic viability: sourced from local and/or small-scale fishing or aquaculture operators Best for food system worker health: see Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, Seafood Social Risk Tool Best for animal health: wild-caught |

Applying an environmental nutrition approach prioritizes purchases with the least human, environmental, and social impacts collectively. When considering the aforementioned information about seafood, wild-caught, underutilized varieties of seafood sourced from local, small-scale fisheries are the most sustainable choice. While there are occasions when the optimal criteria may not be feasible considering available supply and the scale required for institutional purchasing, decisions can be made to move the system toward this model through the development of a food purchasing timeline that evolves as the supply develops.

Sample timeline:

- Year 1: Prioritize seafood with one of the third-party sustainability certifications that Practice Greenhealth determined to be meaningful as a baseline for all seafood purchases. Seek out underutilized wild species from local or small-scale fisheries and allocate a small portion of seafood purchases (e.g. 5%). Work with your vendors to eliminate all purchases of wild-caught and farmed seafood listed as “Avoid” by Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch.

- Years 2-3: Increase the percentage of wild seafood purchases incrementally each year with a focus on sourcing underutilized species from local or small-scale fisheries. Ensure that all seafood purchased meets Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch’s “Good Alternatives” or preferably "Best Choices" list.

- Year 4: Re-evaluate impact to customer satisfaction, budget, and market availability to establish benchmarks for the next three years.

Considerations

Nutrition

Most fish and shellfish are good sources of protein, selenium, vitamins D and B12, taurine, choline, and iodine. Dietary patterns incorporating regular fish consumption have been associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease in adults and improved cognitive development in infants and young children. To achieve many of the health benefits associated with fish, the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that the general population consumes at least 8 ounces (two servings) of a variety of fish and shellfish per week, including some fatty fish, which contain higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids. Some canned seafood (e.g. anchovies) may be high in sodium, so health experts recommend checking nutrient labels to choose lower-sodium options. The nutrient profile of farmed fish varies greatly based on the predatory status of the fish species and feed ingredients.

Pollutants from human industrial activities and agricultural pesticides often end up in streams, rivers, and oceans, causing heavy metals (e.g. mercury, cadmium, and lead) and persistent organic pollutants (e.g. DDT, PCBs, dioxin, and some flame retardants) to accumulate in the tissues of seafood species. Contaminants accumulate most heavily in older, larger predatory fish, so eating fish lower on the food chain (e.g. small forage fish like herring, sardines, and anchovies) is an important way to limit exposure. As with other foods, experts also recommend eating a variety of seafood to reduce contamination from a single source.

Despite the risks associated with consuming fish from any source, nutritional experts agree that in general, the benefits of fish consumption still outweigh the potential health risks from contaminants, but consumers should be aware of fish advisories available nationally. Even for the most at-risk consumers – pregnant or lactating women and young children – the FDA and EPA recommend a minimum of 8 ounces and a maximum of 12 ounces of fish consumption per week, though they are encouraged to avoid fish with the highest levels of methylmercury contamination: shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish.

Sustainability

There is not enough fish for everyone globally to consume the amount recommended for health benefits, even with the growth of aquaculture. Aquaculture systems do not mitigate challenges associated with declining wild stocks and marine biodiversity because of additional environmental impacts with their dependence on marine and terrestrial food supplies. Small wild fish populations in particular are strained due to aquaculture because they are harvested to make fish oil and fish meal that is used as feed.

The environmental impacts of aquaculture depend on the system being used, however no method is without risk. Pollution from fish farms in the form of unused feed, pesticides, antibiotics, and animal waste can impact ecosystems when released into the environment in open-water farming operations. Fish farming can harm wild fish populations by transmitting diseases when the fish are raised in net pens in open water. When escapes occur, farmed fish can compete with native species for food and habitat, and breed with wild fish which can impact overall population health.

A growing area of concern related to the aquaculture industry relates to its contributions to antibiotic resistance. Many countries from which the United States imports farmed seafood (predominantly from Asia) add antibiotic fish baths and feed to prevent disease. Most aquaculture operations in the United States rely on vaccines to prevent disease rather than antibiotics. Thus, in the United States, medically important antibiotics are only used in aquaculture operations to treat diseases for which there is no vaccine. Given the ease with which antibiotics and resistant genes can spread through water, even low and legal levels of antibiotics used in domestic aquaculture operations can significantly contribute to the problem.

Fish transported by air can have significantly high GHG footprints. For those in landlocked communities, fish grown in Recirculating Aquaponic Systems (RAS) which, with improvements in energy efficiency, may prove to be a sustainable option in the future. RAS are considered to have less impact on water quality compared to other systems because wastewater is treated and then discharged or reused within a closed loop system. This structure also makes it virtually impossible for fish to escape into the surrounding environment. The production of fish via RAS is small, and these systems are without a verifiable third-party label to clearly denote this production practice. This makes it challenging for purchasers to prioritize procuring seafood from these systems. Therefore, we cannot include these systems within Practice Greenhealth’s definition of sustainable at this time.

Social

When incorporating more seafood into your menu, prioritize domestic wild-caught options when possible. This will provide the best information on the production and origin of the product as well as the use of chemicals, antibiotics, and labor involved in harvesting. If possible, consider allocating a portion of your budget to purchase items directly from a local fishing cooperative where you can ensure the traceability of the fish and the highest return for the community fisherman. Domestic label certifications indicating local or community-owned fisheries do not currently exist, so you will need to seek this information out from the supplier directly.

Product-specific considerations

There is great variability and uncertainty in asserting definitive species by species recommendations due to the ongoing shifts in seafood stocks. This is why we primarily recommend domestic, seasonal, and underutilized varieties.

Additional high-level recommendations per species include:

- Shellfish/Mollusks

- Shrimp and prawns: When purchasing, prioritize chemical-free domestically farmed or domestic wild varieties but aim to seek out other fish species which are less energy-intensive and require lower-protein feed.

- Clams, mussels, oysters, scallops: These are among the most sustainable seafood options. Some varieties (e.g. Pacific oysters, and mussels) are also high in omega-3 fatty acids.

- Lobster: Avoid lobster caught by bottom trawling, which has a particularly high GHG footprint and depletes marine biodiversity.

- Finfish

- Small forage fish (herring, sardines, anchovies): Forage fish are high in omega-3 fatty acids and when harvested responsibly, are among the most sustainable seafood options. When purchasing canned, choose lower-sodium varieties.

- Mackerel: Mackerel is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids which can have a low GHG footprint, but avoid longline harvested varieties.

- Salmon: Salmon is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids. Prioritize wild-caught varieties from Alaska, but pursue other local fish first if it would need to be air-freighted to reach you.

- Shark: Avoid most species.

- Trout: Trout is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids. Choose wild varieties harvested by troll poles rather than trap nets.

- White fish (cod, haddock, pollock, flatfish, tilapia, etc.): Seek out a variety of species available. Avoid fish caught by bottom trawling.